Tennis elbow is a significant problem that can prevent people from performing athletically and occupationally. Tennis elbow, or lateral epicondylopathy, is an overuse injury that presents as pain and tenderness on the outside of the elbow. While 50 % of tennis players will develop tennis elbow during their lifetime, they represent only 5% of patients diagnosed with tennis elbow. Plumbers, cooks, auto mechanics and other workers with occupations requiring repetitive gripping and grasping activities represent a large portion of people with LE. People of all ages with overuse can acquire tennis elbow, but most cases of the injury occur in people between the ages of 30 and 50.

So, how do we treat tennis elbow? Lateral epicondylopathy should first be treated with rest, ice and activity modification. For more serious cases, prolotherapy and PRP are great options to amplify the body’s healing response. It’s important to note that cortisone or “steroid” injections should not be used as a temporary quick-fix. Patients often report feeling better at the time of the injection, but often end up with poor future outcomes likely related to a combination of tissue degradation from the cortisone and lack of biomechanical alterations (causing them to re-injure themselves).

A great tool to help see the lateral epicondyle is the use of musculoskeletal ultrasound. Ultrasound is the imaging test of choice for the lateral epicondyle, for a reasons:

1. The highest level of resolution and detail

2. The level of detail is particularly excellent for tendon, ligament, and fascia, which are types of tissue that are not always seen clearly on other imaging tests (e.g., x-rays and MRIs)

3. It is the best test for checking motion

4. It is the only imaging test where we can also test for tenderness (since the ultrasound probe is touching the affected area)

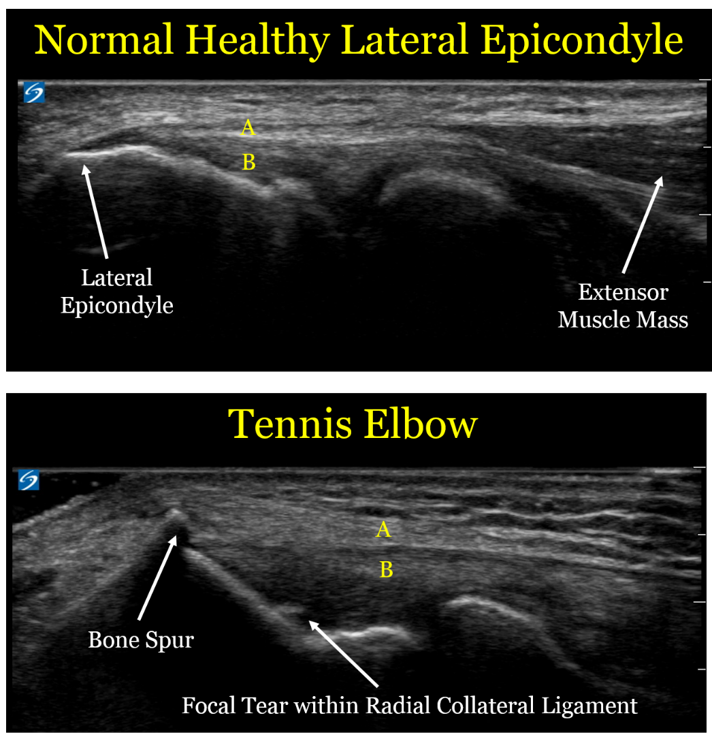

Here are comparison ultrasound images of a healthy lateral epicondyle, followed by the lateral epicondyle of a patient with tennis elbow.

Let's look at the ultrasound images above, first focusing on the upper image of a healthy tendon. One useful thing to see visually is that the muscle mass (the right arrow) looks distinctly different than the extensor tendon (designated by the yellow letter "A"). This is an important detail, since muscle has an excellent blood supply and heals well. Tendon is made of a tight bundle of collagen with a relatively poor blood supply, and may struggle to heal.

In the second image, we can see the anatomic changes associated with tennis elbow:

1. The extensor tendon (A) is thickened and not as well defined as in the healthy elbow. Of note, the patient with the healthy tendon is actually a much larger and more muscular person, so the thickened tendon is in fact a sign of an unhealthy tendon

1. The extensor tendon (A) is thickened and not as well defined as in the healthy elbow. Of note, the patient with the healthy tendon is actually a much larger and more muscular person, so the thickened tendon is in fact a sign of an unhealthy tendon

2. The bone spur created by the unhealthy tendon. We call this an enthesophyte, which is where hte tendon inserts onto the bone. The reason these enthesophytes form is because bone is really a very dense putty, so the enthesophyte is caused by abnormal pulling forces by the unhealthy tendon

3. The part labeled "B" is the radial collateral ligament (RCL), which is underneath the extensor tendon. In the case of the unhealthy patient, there is a tear in the RCL. By definition, a sprain is a tear in a ligament.

4. Of note, there is no "inflammation", which is why the term -itis (e.g., tendonitis) is usually a misnomer. This is an example of a chronic degradation of the extensor tendons and underlying radial collateral ligament, and the more proper term would be tendinosis or tendinopathy.

4. Of note, there is no "inflammation", which is why the term -itis (e.g., tendonitis) is usually a misnomer. This is an example of a chronic degradation of the extensor tendons and underlying radial collateral ligament, and the more proper term would be tendinosis or tendinopathy.

For a sake of comparison, the image below is an MRI

The level of detail is far less. The resolution (which is defined as the ability to distinguish 2 points as distinct) is 5 times higher for the ultrasound. In the ultrasound image, there is a clear distinction between the extensor tendons and the underlying radial collateral ligament, and we can see the individual fibers with great detail. In the MRI, the white arrows show what is essentially a black line, with far less detail. MRI does have some advantages in other contexts (e.g., it sees a wider field of view and can penetrate the bone, so it helps with bone contusions and certain types of joint injuries), but for imaging the lateral epicondyle, ultrasound is a better choice.

So what should we do with these patients?

- Historically, physicians have often performed landmark-based injections to the lateral epicondyle of cortisone. However, moreso than for any other sports injury, repeated data show this is not a good idea. While cortisone injections may help in the short term, they clearly make the injuries worse in the long term.

- Similarly, patients are often advised to use the non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen or naproxen. However, these are also bad choices, because while they can help with pain in the short term, they also prevent healthy collagen formation.

- The best initial treatment option is repeated icing. Ice is a better anti-inflammatory than any medication, and also has other healing benefits.

- Physical therapy is also a mainstay of the best treatment for tennis elbow, where they can focus on exercise protocols designed to promote healing and fix damaging biomechanical patterns.

- For the subset of patients who do not improve with either ice or physical therapy, we often recommend use of proliferative therapy techniques including platelet-rich plasma injections or prolotherapy, which can help induce healthy healing.